Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides - a dinosaur you've likely not heard of!

Share

Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides

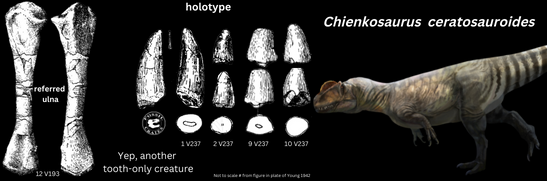

Another theropod you likely haven't heard of, Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides, "Chien Ko Lizard Ceratosaurus-like'' (my best guess at the correct genus translation) was name by Young in 1942 from only teeth. It was yet another dinosaur he named from teeth in the same paper, having also named Szechuanosaurus which you can read about here.

About Chienkosaurus Young wrote, "Four isolated teeth from loc. 47, V 237." and "The Chienkosaurus differs from the Szechuanosaurus not only the smaller size, straightness and bluntness but also by the much stronger inward inclination of the serration of the anterior edge of the teeth."

Here are figures of both Chienkosaurus and Szechuanosaurus teeth for your consideration. The Chienkosaurus teeth all came from the same locality while the Szechuanosaurus teeth were collected from 3 different places. Paleontology was a bit different back then :-).

Young felt Chienkosaurus was related to Ceratosaurus based on the shape of the one complete tooth he found. As I researched this I wondered if Young had seen Ceratosaurus in person, or if he was only working from published literature which, at the time, consisted of precious little. There still isn't a lot of published Ceratosaurus images despite having great material, which is unfortunate as it is such a cool beast! Young only had the Ceratosaurus images below, and a few verbal descriptions, to work with.

Dong et al. (1983) suggested 3 of the 4 teeth (2, 9, and 10 in my figure above) belong to Hsisosuchus, a 10' long crocodylomorph that named in 1953, 11 years after Young named Chienkosaurus. Definitely 3 of the teeth certainly look different from the complete tooth, being wider at the base and more cylindrical. I wonder if Young believed the four teeth were different morphologically simply because he thought they belonged to different positions in the mouth?

Dong et al (1983). stated the remaining tooth isn't diagnostic past theropod, and, because the tooth comes from the same region and geologic layer, Guangyuan, as Szechuanosaurus, they compared V237 (1 in my Chienkosaurus image, the largest tooth) to the Wujiaba material from Zigong, aka Szechuanosaurus, and decided the tooth belonged to Szechuanosaurus, just from a different position in the mouth than the holotype teeth. As you'll read in the Szechuanosaurus description, this is a slippery slope and today both of these taxa are considered nomina dubia.

Additional elements I one could say were referred to Chienkosaurus by Young in the 1942 paper are a caudal vertebra centrum and a probable dorsal vertebra. Young wrote, "Both fit in size with Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides." and is "Probably a dorsal vertebra of a Theropoda, V192.", both statements are not exactly ringing endorsements for Chienkosaurus but keep in mind the Late Jurassic Kuangyuan region of China was unknown fossil-wise, making Young a pioneer, and pioneers break eggs whilst trailblazing. :-)

A left ulna, V193, loc. 47, comes in at 164mm long, 34 mm wide on the distal end, 43 mm on the proximal end. According to Young, "....it fits rather well with the ulna of Ceratosaurus nasicornis" which had been published with a length of 177 mm, 72 mm proximal end width, and 38 mm distal end width. Young writes, "I would prefer to refer this ulna to Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides". It is always scary, to me at least, to refer specimens to taxa based purely on size, we love to see morphological characters that link them together, which is tough when comparing an ulna from one locality with teeth from another. I'm sure today's researchers, if they think about this material at all, shrug and consider all of these teeth and fragmentary bones as representing a theropod, or theropods, of uncertain affinity. Happily, there are much better preserved theropods from this area, like Yangchuanosaurus and Monolophosaurus.

Considering what Young was working with, what would you do? I presume Young never saw the Ceratosaurus material in person, at least not at the time of the publication of Chienkosaurus, so he would have been working with the images above. He was in an area where dinosaurs had never been found before and, almost by definition, these would have been new to science, especially in the 1930s and 40s. There are a staggering number of dinosaurs named from a single bone, or from a smattering of teeth, even to this day. There are no official rules about when one can, or can't, name a new dinosaur. The true test is do researchers use your material in their studies. By naming Chienkosaurus Szechuanosaurus Young brought to the world's attention the fact dinosaurs were present in an area previously unknown.

I'll close out with a thought that has been percolating for awhile. I'm beginning to wonder if the Linnaean system is in need of a tweak. It is a fantastic system overall, and in general serves us well. However, in cases where there is clearly much better material known, perhaps it is time that we insert some level of common sense into the mix? I get the value of paying homage to priority, but when that introduces more complexity than good is that actually helpful? More to follow!

BC